First, there was the land. Well, technically, the Earth began as a sphere of hot, molten material with an atmosphere comprised of volcanic gases. But eventually the Earth cooled and formed a solid crust and liquid water, and once the plate tectonic motors began grinding away, there were continents. Next came life on the land. Well, first there was life in the oceans, and then life on the land. Eventually, after hundreds of millions of year of evolution, we humans came to live on the land. And somewhere in the last 300,000 years or so that Homo sapiens first roamed the Earth, I imagine the first person had the thought “I own this land”, and the great disconnect began — man’s relationship with the Earth and all other living beings changed. What was the driving force behind that thought? Limited resources? Greed? How did we go from living in balance, in community, with all other life forms to the notion that this section of the land, and everything that exists within it, belongs to me to do with as I please?

Aldo Leopold, American writer and naturalist, in his book A Sand County Almanac included a chapter titled “July – Great Possessions”. He begins by noting that, in the record books of the County Clerk, there is recorded 120 acres of land in his name, the extent of “his worldly domain”. He notes, however that the sleepy clerk never looks at his record books before nine o’clock, and what happens on these 120 acres at daybreak “is the question here at issue”. He goes on to describe how, in these early hours, not only the thought of boundaries disappear, but also the thought of being bounded. He describes his “…tenants, negligent in their rent, but punctilious about tenures.” Arising at 3:30 am to sit on his porch with coffee in hand and canine friend at his side, he observes the proclamations: “…at 3:35, the field sparrow avows, in a clear tenor chant, that he holds the jackpine copse north to the riverbank, and south to the old wagon track. One by one all the other field sparrows within earshot recite their respective holdings…before the field sparrows have quite gone the rounds, the robin in the big elm warbles loudly his claim to the crotch where the ice storm tore off a limb, and all the appurtenances pertaining thereto (meaning, in his case, all the angleworms in the not-very-spacious subjacent lawn)”. Leopold continues to log the declarations, from the indigo bunting to a crescendo of other voices — grosbeaks, thrashers, yellow warblers, bluebirds, vireos, towhees, cardinals —”now all is bedlam”. He and his dog then venture out to inspect the holdings. The dog “…is going to translate for me the olfactory poems that who-knows-what silent creatures have written in the summer night.” They find a rabbit, a woodcock, a cock pheasant, a coon or mink, a heron, a wood duck, a deer. Finally, the sun has risen and the bird chorus has run out of breath. The world has shrunk back to those dimensions known to county clerks.

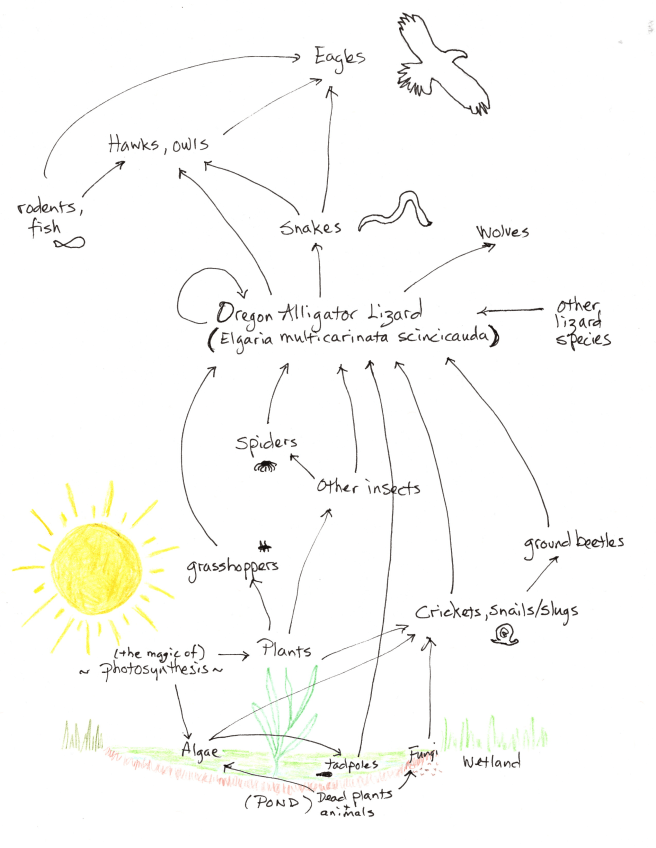

What Leopold is so eloquently opening our minds to is that the land we claim as belonging to us also belongs to the multitude of non-human beings. We occupy land together and our respective claimed territories overlap. These are your closest neighbors. Once we humans come to understand the interconnectedness of this web of life, we wake up to our responsibility to respect the needs of all living beings and not destroy our collective habitats. Indigenous peoples have a long history of understanding this concept and living in harmony with nature., however some branches of humans somehow lost this critical knowledge and began using the land for their own personal gain without regard for the natural world. This group has been quite successful in their endeavors, destroying habitat by logging trees, mining the earth, creating and using pesticides and herbicides, building roads, the list goes on and on. And so we find ourselves here today with an ailing Earth, unable to nurture the life it has created, a sixth mass extinction underway.

The Evolution of Land Ownership in the U.S.

Europeans first arrived on the shores of eastern North America during the 1600’s with the intent of settling on this land that had been claimed by the English crown. Allen Greer, history professor at McGill University, explains that colonists arrived with a familiarity of European agriculture of the time which included the notions of “the commons” and “the waste”. The commons referred to both a place, such as a village pasture, and a set of access rights. The surrounding area beyond local croplands was considered waste, or an “outer commons” area that included the mountains, marsh, and forest that rural people used as rough pasture and foraging areas. A variety of rules and customs governed these areas in the early period of colonial settlement.

Indigenous people had been living in North America for tens of thousands of years, having spread throughout the land, diversifying into distinct Nations. They subsisted on various combinations of hunting, fishing, foraging, and agriculture. America was a patchwork of native commons, each governed by the land-use rules of specific Tribes. To this pre-owned continent came Spanish, English, and French colonists, occupying space, appropriating resources, and developing tenure practices to meet their own needs. The notion of common property was a central feature of both native and settler forms of land tenure. The dispossession of land from the Native American people came about through a clash between the indigenous and the colonial commons.

This clash of the commons occurred gradually over the course of the 17th and early 18th centuries. It was often in the form of Europeans imposing their idea of common land on territory that was already claimed. Colonists, busy with the tasks of clearing forests and building houses, often allowed their hogs and cattle to wander off and fend for themselves, disrupting both the forest ecosystems and the ownership systems of the native tribes. Depending on the number of livestock animals at large, the effects on tribal subsistence could range from simply annoying to utterly devastating. This open grazing tactic represented an implied claim by the colonists to the land itself. When settlers proclaimed, in effect, that the lands’ resources (the wild animals and timber) were open to all, yet the hogs and cattle roaming the same woods remained their private property, they were essentially appropriating the land as their own commons. The margins of subsistence would shrink to the vanishing point for Native Americans living on the colonial commons.

Over the centuries, Native tribes would endure the effects of the roaming livestock and the environmental damage caused by overgrazing in advance of colonists moving into and settling an area. The native commons was constantly under assault as the colonial commons advanced across the face of the continent. What we commonly refer to as “the American frontier” was actually a zone of conflict between Native American commons and the colonial outer commons — a struggle to occupy the same land but with contested customs and rules regulating its resources.

The Native American tribes did not give up their commons without a fight, however. They made efforts to negotiate for shared used of the land and in the early years of settlement, agreements were made. As time went on, colonists refused to cooperate, raising tensions to the point where Native tribes began killing the domestic animals. During the Powhatan resistance of 1622, Natives “…fell uppon the poultry, Hoggs, Cowes, Goats and Horses whereof they killed great nombers.”. The King Philips War in 1675, along with multiple other local wars of that era, broke out in part due to Native tribes’ grievances over livestock. Conflicts and wars with Native Americans continued until the 1920’s. Various treaties and agreements that had been made between the U.S. government and Native tribes to guarantee land rights were broken, and many Tribes were forced to relocate to established Indian Reservations. Native tribes ultimately ceded millions of acres of land to the government through conquest and treaty settlements—cessation and settlement provided the original basis for federal ownership and legal title of U.S. public lands.

It was not only human populations that were driven from their lands by the western advance of settlers. Bison, an estimated 30-50 million of them, thrived on the Great Plains of central North America. In the 17th and 18th centuries, herds of feral horses and cattle had been driven northward from settlers in New Mexico onto the Great Plains, undermining the fragile ecology and facilitating some Native tribes to use horses to more effectively hunt bison. Then, in the mid-1800’s, federal officials who were in the process of forcing Native Americans onto reservations to make way for settlers and railroads, recognized the importance of bison to the Native way of life and hatched a plan to slaughter them to cause hardship for the Natives as well as clear the land for the railroads.They provided free ammunition to hunters and fur traders who, in a frenzied massacre lasting decades, brought the bison to near extinction with fewer than 1,000 individuals left by 1902. In 1905, The American Bison Society was founded to help save bison from extinction and the population has grown to about 30,000 wild bison today.

As the new government continued to acquire land — from the Native Americans, from the British Canadians, from the Spanish Mexicans, from the French, from the wildlife — and encourage settlement across it, the possession of land to individuals and states proceeded in an uneven manner. Provisional local governments would allow people to “claim” certain amounts of land, only to have it taken away as the rules changed. Rumor of gold and silver mines launched hopeful men to far flung areas in hopes of striking it rich through ripping up the land. Congress worked to write laws that would bring order to this chaos. Some of the important legislative acts made in the 1800’s that affected the slicing, dicing, and distribution of U.S. public domain lands are:

- The Land Ordinance of 1785 — Defined the process by which title to public lands was to be transferred to the states and to individuals. Primarily focused on the Northwest Territory, it established a survey system for mapping out uniform squares of property (sections and townships), and allowed settlers to purchase land while also generating revenue for the government. It also provided for public land to be set aside for the states to promote the development of education.

- The General Land Office, 1812 (predecessor of the current Bureau of Land Management) — Established by congress to oversee the surveying and sales of public lands. Most public lands were originally dispersed by the three avenues listed below. In the long run, fences, surveys, registry offices, and other developments associated with private property made their appearance and stabilized new property regimes from which Native peoples were largely excluded.

- Military bounties — land grants to veterans of the Revolutionary war and war of 1812.

- Land grants to states — each new state that joined the union gave up claim to federal public domain lands within its borders but received large acreage of public domain in land grants to be leased or sold by the state to help raise funds for public schools and other public institutions.

- Land grants to build railroads and wagon roads (1860-1880).

- The Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 — Enacted to promote settlement into the Oregon Territory. This was arguably the most generous land act in American History. The act granted, free of charge, 320 acres to any white male citizen settler and another 320 acres to their wife if arriving before Dec. 1, 1850. Claims were also opened to half-breed Native citizens above 18 years old, however, Blacks and Hawaiians were explicitly excluded. A provision allowed half the amount of land to those arriving after the deadline but before 1854. Claimants were required to live on the land and cultivate it in order to obtain the ownership title.

- The Homestead Act of 1862 — Allowed any adult citizen who had never borne arms against the U.S. government to claim 160 acres of surveyed government land. After five years of living on and cultivating the land the claimant obtained ownership title. A shortcut allowed ownership to be obtained after six months by paying $1.25 per acre. More than 270 million acres were granted.

It wasn’t until the 1900’s that any thought was given to make allowances (land claims, in effect) for the non-human beings that had claimed land tenures since time immemorial. Highlights include:

- The Lacey Act of 1900 — the first federal law to protect wildlife. It prohibited interstate shipment of illegally taken game.

- The Migratory Bird Act of 1918 — prohibits the take of protected migratory bird species (unless authorized by the USFWS). The list of protected birds is based on the bird families and species included in the four international treaties that the US entered into with Canada, Mexico, Japan and Russia.

- Migratory Bird Conservation Act 1929 — allowed for the acquisition of national wildlife refuge lands to be managed as “inviolate” sanctuaries for migratory birds.

- Aldo Leopold writes Game Management, 1933 — considered the cornerstone of the conservation movement.

- The Wilderness Act of 1964 — established the National Wilderness Preservation System and authorized congress to designate wilderness areas, giving this definition: “A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain…”. An area of wilderness is further defined to mean “…an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvements or human habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions …”

- National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969 — requires assessment of the impacts of major federal development projects on fish and wildlife.

- The Endangered Species Act of 1973 — established protections for endangered and threatened species and the ecosystems on which they depend. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service manages these efforts in conjunction with other federal, state, local agencies, Tribes, NGO’s and private citizens. Species are listed as threatened or endangered through a regulatory review process that includes a priority system to determine the species of greatest need.

Settlement in the Oregon Territory

Following Lewis and Clark’s Expedition from 1804 – 1806, the first wave of Americans and French Canadians began arriving in the Oregon Country in 1810 with the intent of exploiting the fur potential. Sea otters, river otters, seals, and beaver where the primary targets. These animals were hunted to near extinction within a decade, causing significant ecological destruction. Both Great Britain and the United States laid claim to this region. In 1818, the two nations began negotiations to settle the “Oregon Question”. Unable to come to a settlement, they agreed to joint occupancy. The question was finally peacefully settled in 1843 and the boundary set between Canada and the U.S. at the 49th parallel. Beginning in the 1830’s, missionaries began arriving in the Oregon Country followed by pioneer immigrants arriving from the east via the Oregon Trail with the promise of free land. With the formation of a provisional government in 1843, settlers were allowed to claim 640 acres in a square or oblong form.

Before the passage of the the Donation Land Act in 1850 (see above), the Territorial Delegate to Congress made the case that nullifying Native title to land was the first step necessary to settling Oregon’s land question. After passing this legislation, treaties were renegotiated to remove Indian title to the land and “leave the whole of the most desirable portion open to white settlers.” The consequence of these negotiations led to a race war of sorts in 1852 and 1853 where volunteer white forces ruthlessly drove Native tribes from their traditional hunting and gathering grounds. Regular U.S. Army troops subsequently removed most of the surviving Native bands to newly established reservations. By the time the Donation Land Act expired in 1855, claims were made to 2.5 million acres of land, mostly west of the Cascade Mountains.

In 1866, 3.7 million acres of lands were granted to the Oregon and California (O & C) Railroad Company by Congress to incentivize the construction of a railroad line from Portland to the California border. In 1869, Congress revised how the grants were to be distributed, requiring the railroad to sell land along the line to settlers in 160 acre parcels for $2.50 per acre. These land parcels lie in a checkerboard pattern throughout eighteen counties of western Oregon with alternating sections owned by the railroad company and the federal government (BLM). It became difficult to sell to actual settlers because the land was heavily forested, rugged and remote — not ideal for homesteading. The railroad companies soon realized that the land was much more valuable if sold to timber companies in larger plots. A grand scheme to circumvent settler grants and instead sell to timber companies ensued and by the time the scandal was uncovered in 1904, more than 75% of the land sales had violated federal law. Following a lengthy trial in which 26 indictments resulted in the convictions of politicians, congressmen, attorneys, and land surveyors, the federal government took back, or revested, the remaining land in 1916. Since 1916, 18 Oregon counties have received payments from the federal government at 50% share of timber revenue on those lands. As timber revenue decreased, the government added federal revenues to make up the losses to the counties. Several of those counties have come to rely on that revenue as an important source of income for schools and county services. The “timber wars” continue today.

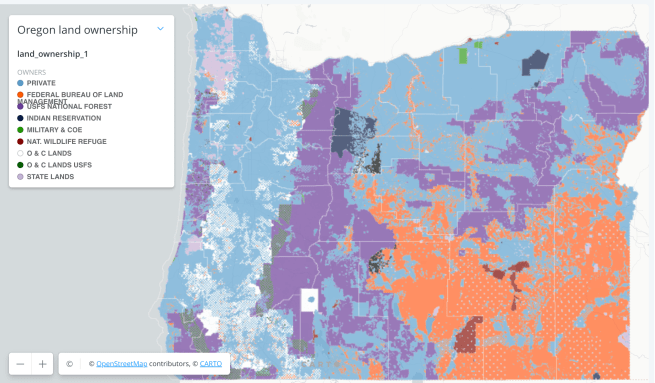

U.S. Land Management Today

Fast forward to today and we find the U.S. to be a patchwork quilt of land owned by private, state, and federal interests. Our federal lands are managed by the following agencies whose priorities change at the direction of the current U.S. president and their administration leaders. I’ve listed below only the federal departments and agencies that are involved with land management to show their structure, relationships, and purpose. Inset bureaus and agencies are embedded within the department they fall under. Many land and natural area designations are managed collaboratively by both federal and local entities.

- Department of Interior (DOI) —Protects and manages America’s natural and cultural resources and plays a central role in how the U.S. stewards its public lands.

- Bureau of Land Management (BLM) — Originally titled the General Land Office (see above). Created to support the goal of westward migration and homesteading. Today, the BLM manages ~10% of public land and ~30% of mineral estate (surface land may be sold with the BLM retaining the underground mineral rights). This land was originally described as “land nobody wanted” because homesteaders passed it by. Now, ranchers hold leases and permits to graze cattle on 155 million acres.

- National Conservation Lands — Includes National Monuments, National Conservation Areas, Wilderness Areas, Wilderness Study Areas, Wild and Scenic Rivers, National Scenic and Historic Trails, Conserved Lands of the California Desert, and more.

- Most Oregon and California (O & C) Revested Lands (see also USFS below) — The history of this land designation is summarized above under “Settlement in the Oregon Territory.” 2.4 million acres remain of the original O & C lands. These are multi-use lands including forests, recreation areas, mining claims, grazing lands, cultural and historical resources, scenic areas, wild and scenic rivers.

- National Conservation Lands — Includes National Monuments, National Conservation Areas, Wilderness Areas, Wilderness Study Areas, Wild and Scenic Rivers, National Scenic and Historic Trails, Conserved Lands of the California Desert, and more.

- National Park Service (NPS) — Manages 433 individual parks covering 85 million acres in all 50 states. Includes National Parks, National Monuments, and other natural, historic, and recreational properties with various title designations.

- U.S Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS): —The nations oldest conservation agency, dating back to 1871, whose primary responsibility is the conservation and management of fish, wildlife, plants and their habitats.

- National Wildlife Refuge System — Includes more than 570 refuges in the U.S., this system, founded in 1903, was established to conserve native species.

- Bureau of Land Management (BLM) — Originally titled the General Land Office (see above). Created to support the goal of westward migration and homesteading. Today, the BLM manages ~10% of public land and ~30% of mineral estate (surface land may be sold with the BLM retaining the underground mineral rights). This land was originally described as “land nobody wanted” because homesteaders passed it by. Now, ranchers hold leases and permits to graze cattle on 155 million acres.

- Department of Agriculture (DOA or USDA) — Provides leadership on food, agriculture, natural resources, rural development, nutrition, and related issues. Includes 29 agencies including the following related to land management:

- Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) — The USDA’s primary private agricultural lands conservation agency. They generate, manage, and share data, technology, and standards that enable partners and policymakers to make decisions based on objective, reliable science.

- U.S. Forest Service (USFS) — Provides leadership in forest research including sustainable management, conservation, use, and stewardship of natural and cultural resources. Administers 154 national forests and 20 national grasslands (~25% of national lands).

- Some Oregon & California (O & C) Revested Lands (see also BLM above) — Running across sections of seven National Forests in Oregon are the remainder of almost a half million acres of O & C lands. These holdings are different from BLM O & C lands in that they overlap with National Forest land and so are managed and governed by the USFS, yet remain O & C territory for the purpose of revenue sharing to the O & C counties. They include designated Botanical, Research Natural Areas, National Wild and Scenic Rivers, and Inventoried Roadless Areas. They are referred to as “controverted” lands by timber lobbyists and those who want to include them in BLM O & C legislation in order to avoid National Forest regulations.

- Department of Defense (DOD) — Provides the military forces needed to deter war and ensure our nation’s security. Includes ~27 million acres of land on 338 military installations.The Sikes Act of 1960 requires the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, State Fish and Wildlife agencies, and military installations across the nation to work collaboratively to conserve natural resources. These lands support the preservation of ecologically important native habitats making military installations somewhat of a haven for fish, wildlife, and plants.

- Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) — Comprised of both civilians and soldiers, there are three main branches: the Engineering Regiment, Military Construction, and Civil Works. The Engineering Regiment and Military Construction branches manage the engineering needs of the military. The Civil Works branch has three arms: navigation, flood and storm damage protection, and aquatic ecosystem restoration. This branch also oversees the Clean Water Act. As the nation’s environmental engineer, they restore degraded ecosystems, construct sustainable facilities, regulate waterways, manage natural resources, and clean up contaminated sites from past military activities. Other activities include: dredging waterways, devising hurricane and storm damage reduction infrastructure, protecting and restoring the nation’s environment along many major waterways, clean hazardous, toxic, or radioactive waste sites.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) — Has a broad mission to “protect human health and the environment”. To accomplish this they write and enforce regulations to implement laws written by congress, give grants, study environmental issues, work with partnership organizations, teach, and publish information.

- Oregon Department of State Lands (DSL) — Upon each state’s admission to the union, the federal government ceded to the state two sections of each township to generate revenues for a Common School Fund, a trust fund for the support and maintenance of public schools. In 1859, Congress granted Oregon 3.4 million acres of land. Today, approximately 681,000 acres of school lands remain. These lands are managed by the State Land Board which leases and sells land to generate revenue for the Common School Fund.

Interestingly, when you read the mission statements of many of the above organizations, they mention caring for and restoring the land, protecting native species and their habitats, cultural heritage, etc. — goals we inherently know to be necessary and good. Yet many call out that this work is “in service of the American people”. It is clearly evident that we have long lost sight of the fact that people share the Earth with countless other living beings: the plants, animals, fungi, bacteria and protists. These mission statements need to be rewritten to state their work is “in service of all life on Earth”. I would also suggest that these organizations, who oversee the stewardship of our remaining public lands, should somehow be disconnected from the vagaries of our political process in order to gain stability and a long-lasting commitment to preservation.

In addition to the federal agencies, there are also approximately 13,000 Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) listed as operating in the U.S. that focus on protecting Earth’s environment. How is it that so many governmental and non-governmental organizations exist, many with essentially the same mission statements and yet, still, our Earth’s natural environment continues to be degraded to the point where we are held to bear witness to the sixth major extinction of species? Why is it that non-governmental organizations, sometimes find it necessary to file lawsuits against our governmental organizations for their failure to follow their own regulations designed to protect the environment? Why is it that we continue to allow for business interests of all kinds to operate on land in a way that knowingly destroys and pollutes habitats, greatly contributing the decline of species?

Broken Relationships, the Deeper Problem

In this time of rapid climate change, sea levels are rising and land that humans have built their structures on and assumed “ownership” of, is being reclaimed by the oceans. Weather has become more extreme with both droughts causing unrelenting thirst and loss of life due to the lack of water, and flooding causing a sudden sweeping away of the lands’ table-setting, leaving behind devastation and ruin. Wildfires that used to be natural and beneficial to the land are now more intense, burning both forests and urban areas, consuming anyone who cannot move out of the way fast enough, destroying habitat, and releasing toxic particles into the environment. The earth is being enveloped in a permanent layer of plastic, its micro particles now found within the bodies of all animals, including us. Humans are finally coming around to making the connections between our past and current behaviors and the health of the planet, forcing a re-think of our individual relationships to the land and how we care for it. Our current relationship to the Earth is broken — so too, many of our human relationships are broken. Our Civil Society is fraying; many of our actions can no longer be considered “civil”. Is there a connection? This moment calls for each of us, as individuals, to reflect on how we can repair these broken relationships. Many among us are showing the way — it’s time to listen and engage in reparation.

Making the Connection

Coming back around to the wisdom of Aldo Leopold, who echoed the wisdom of Indigenous Peoples, the original stewards of the Earth’s gifts, by promoting understanding of what he termed the “Land Ethic”. This term is best defined on the Aldo Leopold Foundation website:

A land ethic expands the definition of “community” to include not only humans, but all other parts of the Earth as well: soils, waters, plants, and animals — “the land”. In a land ethic, the relationships between people and land are intertwined; care for people cannot be separated from care for the land. Thus, the ethic is a moral code of conduct that stems from these interconnected caring relationships.

Many other voices have since joined Leopold’s in reminding us of our place as part of Earth’s community. Robin Wall Kimmerer, in her best selling book Braiding Sweetgrass, shows us how, through the lenses of both science and traditional ecological knowledge, we can come to embrace a reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world — we should not only take what is given from the land, but also show gratitude for the gifts and give back to the land in the form of tending and protecting. We must continue our push to understand the complexity and connections of the natural world while also listening to the indigenous voices among us who continue to share their ancestral knowledge of how to tend and protect the land. We are starting to listen and remember those lessons. As Kimmerer points out, “each of us comes from people who were once indigenous”.

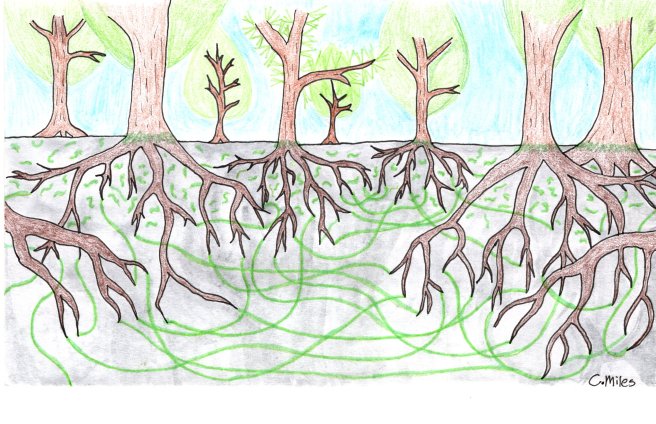

Listen to the voices of those among us, human and non-human, who are showing the way. There’s Suzanne Simard, author of Finding the Mother Tree, and her work to enlighten us on the lives of trees and their large, interconnected community. There’s Merlin Sheldrake, author of Entangled Life, and his insights, amazing photos and education about the complex lives of fungi in the soil and how it supports and sustains nearly all living systems. There’s Zoë Schlanger, author of the newly published book The Light Eaters, opening our understanding of the complex lives of plants. And, when we take the time to pause and listen, we’ll hear the voices of our non-human relatives sharing how they collaborate within their communities to care for the land. Scientists and writers are sharing with us the gift of their hard work in uncovering the mind-blowing agency, intelligence, and consciousness of the living world. It is incumbent on all of us to pay attention and come together to stop harming the land and to instead start nurturing it.

Even those who deny knowing it, know that the earth’s resources are limited. Healing begins with recognizing there must be limits to our taking and over-consumption, acknowledging that it is possible for all people to work in community for the common good. We must agree that our land is a common resource needed for all beings to thrive, and care for it as we care for other things that we value dearly. Yes, we may have paid money to live on a piece of property, but what we have agreed to in that purchase is not only the right to set up a home or business in an allotted space, but also a responsibility to be good stewards of that section of the earth — to care for and tend that section of land so that all life can thrive.

Just as the trauma of past injustices and slaughter lives on in the DNA and spirit of the Native American peoples of today so, too, does the trauma live on in the DNA and spirit of the bison and other animals nearly hunted to extinction by humans. Bison now not only watch over their shoulder for their usual predators, but also keep an eye out for the two-legged predator carrying a gun. How can reparations be made? We cannot undo the destructive actions that were taken by our ancestors in the past, but we have the agency to acknowledge the pain and injustice brought upon so many beings and commit now to act to protect Earth’s precious resources that are necessary for all life to thrive.

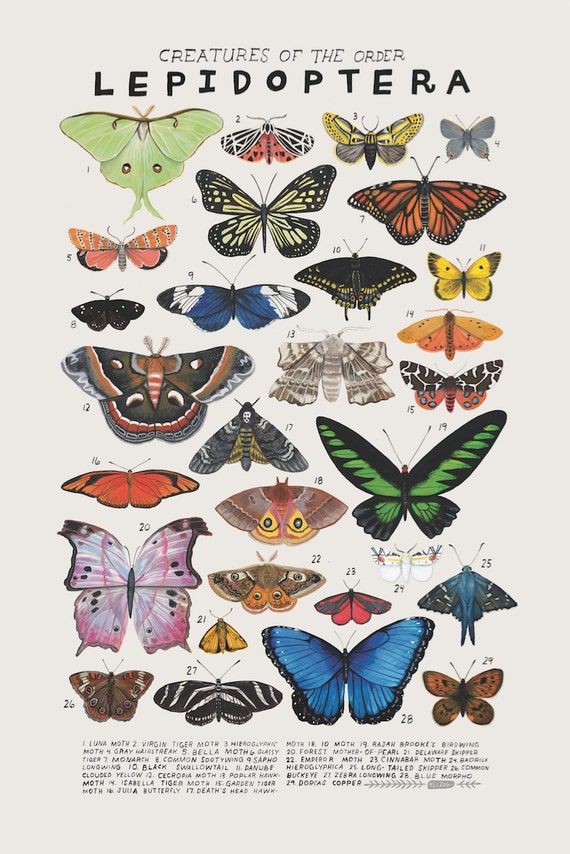

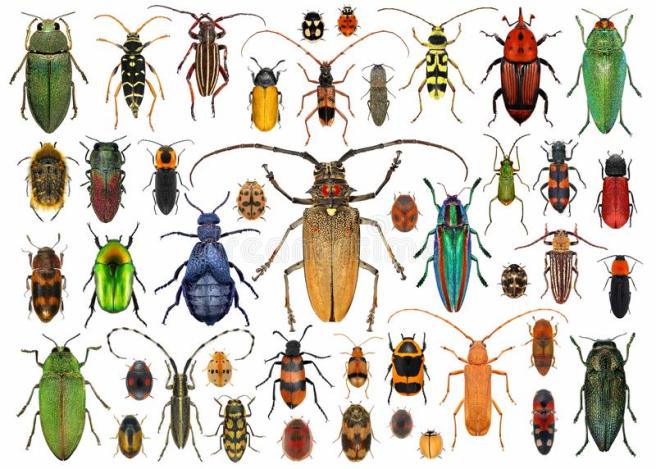

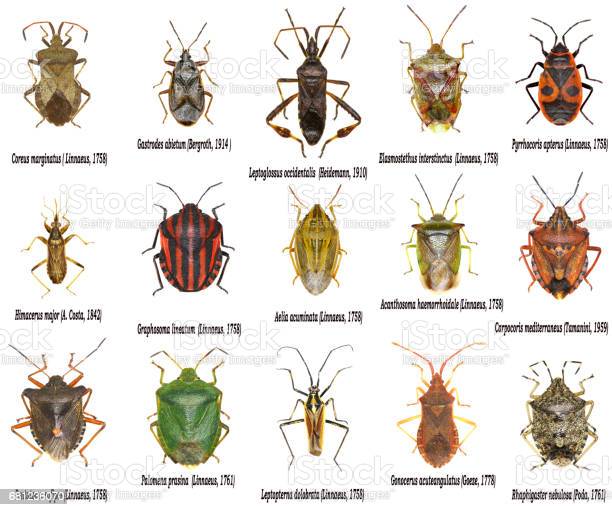

We must first come together in common cause, to protect earth’s remaining intact natural habitats. Secondly, we must restore degraded habitats, as best we know how, to a semblance of what they once were in order to provide opportunity for life to thrive. Thirdly, we must educate others of the necessity of this work. Lastly, let us lend our voices to the voiceless — the furred, the feathered, the scaled, the antennaed — in advocating for their needs. They have been missing from the stakeholders table where property rights decisions have been made. Let us sit at that table for them and speak up for the protection of their homelands, as well as our own. Join us, won’t you?

References

- Leopold, A., A Sand County Almanac (1949), Oxford University Press

- Orr, E, et. al., An Environmental History of the Willamette Valley (2019), The History Press

- Oregon and California Railroad Revested Lands , Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oregon_and_California_Railroad_Revested_Lands

- “The National Forest O & C Lands No One is Talking About”, Retrieved from https://kalmiopsiswild.org/threats/national-forest-oc-lands/

- Facemire, Challie, et.al. “Biodiversity Loss, Viewed Through the Lens of Mismatched Property Rights” , International Journal of the Commons, Retrieved from: https://thecommonsjournal.org/articles/10.5334/ijc.985#5-case-studies

- Moon, K., et.al., Coupling property rights with responsibilities to improve conservation outcomes across land and seascapes, Conservation Letters (Sept. 2020), retrieved from: https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/conl.12767

- Key Messages on Human Rights and Biodiversity from United Nations Human Rights, retrieved from: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/ClimateChange/materials/KMBiodiversity26febLight.pdf

- What are the Rights of Nature, GARN (Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature), retrieved from: https://www.garn.org/rights%20of%20nature/

- Land Grant, United States, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_grant

- America’s Public Lands: origin, history, future, Public Lands Foundation, Arlington, VA (Dec. 2014): https://publicland.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/150359_Public_Lands_Document_web.pdf

- Gershon, L., Yes, Americans Owned Land Before Columbus, JSTOR Daily (March 2019): https://daily.jstor.org/yes-americans-owned-land-before-columbus/

- Greer, A., Commons and Enclosure in the Colonization of North America, The American Historical Review, Vol 117, No. 2 (2012), pp. 365-386: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23310740?mag=yes-americans-owned-land-before-columbus&seq=1

- History of Native Americans in the United States, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Native_Americans_in_the_United_States

- Bison Bellows: Wildlife Conservation Society and American Bison Society, National Park Service, retrieved from: https://www.nps.gov/articles/bison-bellows-4-7-16.htm

- The National Forest O&C Lands No One is Talking About, KalmiopsisWild.org: https://kalmiopsiswild.org/threats/national-forest-oc-lands/

- The Land Ethic, uniting ecology and ethics by living in community with the land, The Aldo Leopold Foundation, retrieved from: https://www.aldoleopold.org/about/the-land-ethic

- Vaughan, C.C., A History of the United States General Land Office in Oregon, retrieved from: https://www.blm.gov/or/landsrealty/glo200/files/glo-book.pdf

- American Indian Wars, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Indian_Wars

- Gibbons, W., Oregon Donation Land Law, Oregon Encyclopedia, retrieved from: https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/oregon_donation_land_act/

- United States Army Corps of Engineers, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Army_Corps_of_Engineers

- U.S. Department of Interior, website retrieved from: https://www.doi.gov/

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, website retrieved from: https://www.usda.gov/

- U.S. Department of Defense (accessed prior to installation of new Defense Secretary Hegseth), website retrieved from: https://www.defense.gov/

- Oregon Department of State Lands, website retrieved from: https://www.oregon.gov/dsl/pages/default.aspx

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, website retrieved from: https://www.fws.gov/