Estuaries are one of the “in-between” places, a liminal space, a place where there’s a mixing of elements, a necessary cooperation among those who call them home, a toughness of spirit to live in conditions outside the norms. They are vital to the health of marine ecosystems. They hold the space where a river meets the ocean. They hold a mix of freshwater that includes nutrients, pollutants, and soils collected from the rivers, creeks, and streams of the land as well as saltwater from the sea. The high nutrient load coming from the rivers, mixed with tidal flows and plenty of sunlight make estuaries an ecosystem where numerous organisms can thrive. They provide a necessary shelter and refuge for many species of migratory animals, serving as nursery and feeding grounds for many fish and shellfish. They help to buffer the impacts of climate change by moderating storm surges and sequestering carbon. The combination of physical complexity which provide numerous habitat types and abundance of food make estuaries a biodiversity hotspot.

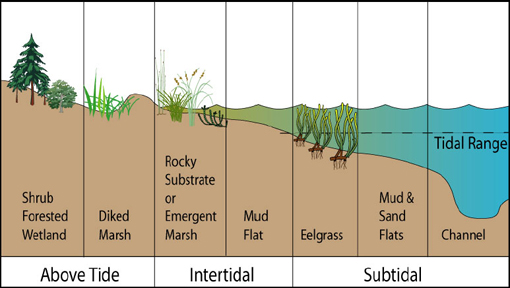

Estuaries are physically complex; there is high variability in both the physical geomorphology and the salinity gradients found in estuaries. Dense, salty seawater flows in during a high tide and sinks to the bottom of the estuary. Warmer, less-dense, freshwater from rivers flow into and over the salty layer. Physical features include deep channels, shallow brackish waters, rocky reefs, exposed sand and shell banks, and intertidal sand and mud flats. Once or twice a day, tidal currents move salt water into and out of the estuary. The amount of mixing of these two different waters is dependent on several variables including the speed and direction of the wind, the tidal reach, the estuaries shape, and the volume and flow rate of river water entering the estuary.

This environment creates a variety of unique habitat types that have allowed for a rich biodiversity of life to evolve, adapt, and interconnect. These organisms interact as if in an intricate dance, moving in and out of various spaces and switching partners as a better opportunity presents itself. Each dancer has a role to play on this estuarine dance floor. The evolution (or coevolution) of each species to begin life, grow and thrive, allowing for reproduction before dying, has given an opportunity for this disparate mix of organisms to create a beautiful dance movement on this estuarine stage. Let’s zoom into an Oregon coast estuary and take a virtual spin around this stage to better understand the physical space and the dynamics of the life it supports.

Open Water Habitat

The open water habitat is dominated by that which we cannot see — phytoplankton and zooplankton. Plankton refers to organisms, typically microscopic, that cannot swim on their own and tend to drift with the currents and tides, however some larval species have mechanisms to resist being swept out of the estuary. They are the tiny plants and animals rarely seen or considered; yet they are the organisms that are the basis of all life on Earth. Phytoplankton, including diatoms, dinoflagellates, and other protists (a diverse collection of organisms that are not animal, plant, bacteria, or fungi), are anchoring the base of the food web. Their numbers vary seasonally. A rich diversity of zooplankton also occupies the estuarine open water, some temporarily and some permanently. Their numbers can vary substantially on a tidal and seasonal basis. They include copepods, hydromedusae (tiny transparent jellyfishes), larvae of barnacles, crab, and shrimp, larval and juvenile forms of fish species, etc.

A very unique and interesting habitat within any open water area is the surface microlayer (called the sea surface microlayer in the open ocean).The surface microlayer is a hydrated, gel-like boundary layer composed of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids about 1 mm thick. It is where chemical gas exchange occurs between the atmosphere and the underlying waters — measurably distinct chemical, physical, and biological properties are found in this layer as compared to the underlying water. Living within this thin surface microlayer — on top, attached to the underside, or within the layer, — is a distinct microbial community of organisms collectively termed neuston. Neuston in estuaries include microscopic and macroscopic phytoplankton, bacteria, protists, and a wide variety of zooplankton. In late spring and summer, neuston are blown into the estuary from the open ocean and are thought to contribute to the food web of the organisms that inhabit estuaries. The neuston provide a food source for the zooplankton lower in the water column as well as for migrating birds.

Actively swimming organisms are referred to as nekton. In an estuary, this group includes mainly mysids (small, shrimp-like crustaceans that feed on algae, detritus, and zooplankton) and midwater fish. Mysids are sensitive to water pollution so are sometimes used as an indicator species for water quality. The mysid species found in estuaries can tolerate salinity conditions that range from freshwater to entirely marine. Estuaries provide refuge and feeding grounds for the postlarval, juvenile, and adult stages of numerous fish species including perch, herring, smelt, shad, anchovy, salmon, cutthroat trout, etc. Seals, sea lions, and occasionally whales will move into estuaries from the ocean, seeking food and shelter. They are also known to serve as nurseries for some species of juvenile fish. In general, the types and numbers of fish species varies seasonally with the highest numbers in the summer months and the lowest numbers in the fall and winter.

Eelgrass Habitat

Oregon’s native eelgrass beds, Zostera marina, play a significant role in our estuarine environment. Yes, this plant is a keystone species. They are found in the lower intertidal zones and are exposed only during the lowest of tides. This flowering plant requires cold water (50 – 60oF) in order to thrive and can grow to over 6 feet tall. They form dense meadows that provide organic matter to the food web, stabilize sediments, absorbs CO2 and methane, trap detritus, improves water quality and clarity, absorbs pollutants which helps prevent algal blooms, and provide shelter and forage habitat for invertebrates and fishes.

The eelgrass meadow habitat is highly complex and biologically diverse. Only waterfowl directly consume the eelgrass blades, but many organisms consume it once it has broken down into detritus. Epiphyte is the term used for any fixed organism living on the surface of a plant. On eelgrass blades, algae is the most abundant epiphyte and serves as the base for many food webs. It is directly consumed by grazers such as snails and sea slugs. Other epiphytes include bacteria, fungi, sponges, hydroids, crustaceans, etc. Over time, as the epiphyte load on the grass blade increases, the blades slough off the plant which then allows more light to reach the plant. In a healthy eelgrass ecosystem, the epiphyte/grazer/predator interactions keep the system in balance. Too much algae (caused by too many nutrients entering the system — think fertilizers) can lead to die-offs if the plant cannot receive enough light. At high tide, weaving in and out of the blades, a diverse group of nekton dance on this stage, feeding and sheltering. In Oregon, you’ll find juvenile rockfish, Bay pipefish, Shiner surf perch, Saddleback gunnel, among others. On cue, migratory birds swoop in to sit at this table.

Pacific herring swoop in to the eelgrass beds in mass along the Oregon coast and during one day in February lay enough eggs on the eelgrass to totally change the color and appearance of the beds. This spawning activity does not go unnoticed by other living creatures. The herring lay their eggs in one day and then are gone but on that day, seals, sea lions, cormorants, surf scoters and other animals descend to feed on the herring. Estuaries are THE most biologically productive areas on the planet!

Tidal Channel and Subtidal Habitat

Upland creeks drain higher areas of the coast toward the ocean shore and at some point they become tidal — this is where the tidal channel habitat comes onto the stage. These areas form as the tide ebbs and allows the river to incise a channel as it flows from the inland to the shore. When the tide comes in, large areas of water can be filled with the mix of salty and fresh water — a twice-daily show. High tidal flow will maintain the channel whereas slower flow velocity will lead to the channel filling with sediment.

Once again, we find a high level of species diversity in the tidal channels and subtidal habitats. Subtidal zones are the area close to shore that remains constantly submerged. Bull kelp can be torn loose from rocky reefs outside the estuary during storms and carried into estuaries, their strong holdfasts often still carrying with them the rocks they’re attached to. These rocks collect in the subtidal sand and mud to add to the habitat structure. The biological assemblage dances on and off this stage in response to seasonal and annual differences in the extent of oceanic influences and freshwater input. Dominating the subtidal zone are the infaunal (burrowing) invertebrates. Common epifauna (living on the surface sediment) are shrimp, crab, snails, bivalves, sea cucumbers, sand dollars, etc. Sea pens are an important emergent species found only in quieter subtidal habitats with muddy bottoms. Common fish include several species of flatfish, and burrowing forage fish such as Pacific sand lance and sandfish that like to cover themselves to hide in the sediment. Both juvenile and adult Dungeness crab forage here and may hide in the soft sediments. Many juvenile fish species use this habitat as a nursery area and become prey themselves for larger fish and birds.

Sandflat and Mudflat Habitats

Here in the sandflats and mudflats of the estuary, the scene on the stage also changes twice daily. As the tides ebb and flow, these habitats are either covered in water or exposed to the atmosphere. Mudflats are composed of very fine grain particles and can be found in the more sheltered areas, typically where rivers are making their entrance and depositing their load of sediment as they reach a place of a lower energy. Polychaete worms (marine/estuarine worms called “bristle worms”), snails, and molluscs (burrowing clams and shrimp) are happy here along with the ubiquitous microalgae, diatoms, bacteria and others. Sandflats are typically found closer to the open ocean where wave action prevents the deposition of finer silt. Here, looking closely, you will find more crustaceans, and scanning the horizon, you will see the shorebirds coming in to dine on those crustaceans.

Salt Marsh Habitat

At the fringe of our estuarine stage, above the tidal flats and below the uplands, lie the salt marshes. Think of this space as the ecological guardian of the coast. These coastal wetlands are flooded and drained by the tides, exposing a surface of deep mud (often with a high salt content) and thick peat (decomposing plant material). Tangled marsh plant roots help to stabilize the muddy bottom and trap debris. Salt marshes protect shorelines from erosion by creating a buffer against wave action. They also mitigate flood waters, filter runoff and excess nutrients, serve as carbon sinks, and provide a big assist in maintaining water quality. Crab, shrimp, and many finfish enter the salt marshes looking for shelter, food, and nursery grounds. A variety of invertebrates inhabit the salt marsh community, however, there is less diversity and biomass as compared to adjacent tideflats and channels. Migratory birds also use the salt marshes for resting and forage habitat.

The habitats I’ve described above are all found on the stage of the estuary. However it is important to recognize that this stage is actually a complex mosaic of ever-changing scenes with Mother Earth and her moon operating as stage managers. The open ocean water enters and leaves at the direction of the moon with the sandflats, mudflats and eelgrass appearing and disappearing on cue. Earth conducts the rest of the variables that shape the estuary; rainfall drives water and sediment input from inland rivers leading to expansion or shrinking of the stage while the rivers’ energy carves the channel. Wind and waves force ocean water with it’s associated components into the estuary. The cast of characters have been dancing in their roles for thousands of years and have adapted their responses to this direction. Each depends on the other to play their roles so that all can thrive.

Estuary Habitat Use by Mammals

Numerous land, river, and ocean mammals come to eat and shelter at the estuary margins, including elk, bear, deer mice, vagrant shrew, racoon, deer, beaver, muskrat, nutria, river otter, harbor seals, sea lions, and occasional juvenile elephant seals. Beaver often set up shop along the shorelines of estuaries, building dams in the tidal creeks and freshwater wetlands which flood and provide pond habitat for many other species to thrive (read more about the amazing engineering feats of beaver in my previous post “Beaver: the Ultimate Keystone Species“).

Invasive Species

To the surprise of no one, you’ll have no trouble finding invasive species in an estuary environment. Invasive species have exploded globally over the last several decades and are a significant driver of native plant and animal extinctions. Globally, at least $423 billion is spent annually in an effort to control the worst of them. Invasive species are opportunistic organisms that are filling a niche that was created for them by humans, often by tagging along from one location to another on transport carriers (such as boats), or having been purposefully introduced to a new habitat location in which the alien species has no predators and causes fatal disruptions to local food webs. Commercial oyster cultivation practices provide another mechanism for the introduction of invasive species in estuaries through importation of non-native seed oysters. Keep in mind that, in general, although some invasive species can take over and totally alter a habitat in a destructive way, others may alter a habitat in a way that is different but not necessarily destructive, or may even be totally benign.

And so, dancing uninvited onto our estuarine stage along the Oregon coast you’ll find these characters, among others:

- European Green Crab — native to Europe, these crabs have been introduced to many coastlines around the world, likely by hitching a ride in the ballast water of ships. They were first observed in San Francisco Bay in 1989 and expanded upward to the Oregon coast and beyond in 1997. They are voracious predators that feed on muscles, oysters, crabs, shrimp, small fish, and a variety of other small marine organisms. They also bite the base off native eelgrass, effectively killing the plant. On the west coast, they have been limited to upper estuarine environments, in part because of predation by native rock crabs and competition for shelter with a native shore crab. But as their populations grow, this situation is changing and being closely watched. I recommend watching Oregon Public Broadcasting’s short video: Green Crabs are Invading the Pacific Northwest Coast

- Japanese eelgrass — it is thought that this species was introduced to the Oregon coast through commercial oyster cultivation activities. In Oregon estuaries, this species has changed thousands of acres of mudflat habitat into rooted aquatic vegetation and dramatically changed the composition of infaunal invertebrate communities. Results of experiments in South Slough suggest that dense beds of Japanese eelgrass modify the intertidal mudflats and serve as a refuge for some species (Polychaetes) but may increase mortality of others (juvenile crabs).

- Atlantic smooth cordgrass — this species first arrived on the West Coast in Willapa Bay, WA over a century ago and has been spreading rapidly in WA and OR. It reduces mud flat habitats, disrupts nutrient flows, displaces native plants and animals, alters water circulation, and traps sediments at a greater rate than native plants, altering the elevation and the resulting habitats. This is similar to the process humans have used of diking and draining that has been used to create agricultural land.

Making the Connection

As the sun starts to slip behind the western horizon, the curtain begins to draw over the estuary. Some creatures tuck away into their sheltered niches to await a new day, some nocturnal types stir in anticipation of the “after dark” show. Estuaries themselves have a life cycle. They last arose about 12,000 years ago as natural climate change shifted global temperatures causing glaciers to recede and sea levels to rise. Our estuaries of today have remained relatively stable (with the exception of human interventions such as diking and filling) for the past 6,000 years. Once formed, estuaries become traps for sediments carried in by rivers and sand from the ocean floor carried in by tides. In mid-life, estuaries become more complex, allowing for colonization of new plant and animal communities and their evolution to the changing environment over time. The pace of change is driven by how quickly the estuary fills with sediment — if more sediment comes in than goes out, the estuary will eventually fill and become dry land with river channels being diverted to birth a new estuary. However, an estuaries’ life may also end abruptly due to tectonic activity — earthquakes that suddenly raise the land, for example, cutting it off from tidal activity.

Human impact can shorten the natural life span of an estuary. Sedimentation is sped up by tree and brush removal for logging or development. Excess nutrients from fertilizers lead to algal blooms which deplete the water of oxygen and release deadly toxins. Toxic substances like chemicals and heavy metals that enter our waterways through industrial discharges, yard runoffs, streets, agricultural lands, and storm drains have the greatest negative impact on the health of estuaries. These substances are toxic to all estuarine life and they make their way from the bottom to the top of the food web. And, as we humans consume some of these organisms, those toxins are coming back to us.

Climate change is driving warming and acidification of our oceans. As glaciers and the polar ice caps melt, sea level rise causes higher, more extensive inundation of ocean water into the estuary, altering the delicate balance of plant and animal interactions. More frequent and extreme weather events compound this problem by forcing increased sediment-filled river runoff and altering hydrology patterns.

The choices we make every day, what we chose to consume, what we chose to discard, how we regard and show respect for the natural world, or disregard and turn a blind eye to the destruction being wrought, ripples out into the world from wherever we are. Those ripples reach the estuaries through the water all around us, through the atmosphere we are impacting. Many people have experienced the beauty and dynamics of an estuary, however many others have never had this opportunity. Yet the choices of each and every person send out the ripples. There are national and local networks in place that provide funding to conduct critical research and recommendations on how we can protect these essential habitats, yet it is knowledge and education that drives people to make better choices for our natural world. By sharing this post, you are sharing some of the necessary education — thank you!.

References

- “Estuaries”— Oregon Conservation Strategy. (2016). Retrieved from: https://oregonconservationstrategy.org/oregon-nearshore-strategy/habitats/ons-estuaries/

- Sawkar, Anu, Crag Law Center. (December 8, 2022). “Eelgrass and How to Protect It” [webinar]. Oregon Shores Conservation Coalition. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LCh8XARGG3c

- Johnson, Phillip, Executive Director of Oregon Shores Conservation Coalition. (May 27, 2021). “Eelgrass in in Oregon’s Estuaries: Natural History and Planning“. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SXShr0RZftE

- Science Learning Hub – Pokapū Akoranga Pūtaiao. “Life in the Estuary“. (June 12, 2017). Retrieved from: https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/1230-life-in-the-estuary

- Schooler, S, et.al. (2022). “Status of the 5-spine (aka Green) Crab (Carcinus maenas) in Coos Bay: Monitoring Report 2022”. South Slough Reserve. Retrieved from: https://www.oregon.gov/dsl/SS/Documents/Green_Crab_report_2022_Coos_Bay_SSNERR.pdf

- Rumrill, S. “The Ecology of the South Slough Estuary: Site Profile of the South Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve“. Retrieved from: https://coast.noaa.gov/data/docs/nerrs/Reserves_SOS_SiteProfile.pdf

- Seagrass.li, Long Islands Seagrass Conservation Website. Retrieved from: http://www.seagrassli.org/ecology/fauna_flora/epiphytes.html

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “Estuaries Lessons“. Retrieved from: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/tutorial_estuaries/

- Land, Air, Water Aotearoa (LAWA). “Factsheet: Understanding Estuaries”. Retrieved from: https://www.lawa.org.nz/learn/factsheets/estuaries/understanding-estuaries/#:~:text=When%20young%2C%20most%20estuaries%20have%20deep%20basins%20and,space%20allows%20saltmarsh%20vegetation%20and%20mangroves%20to%20establish.

- “Neuston“. en.wikipedia.org

- “Subtidal soft bottom“— Oregon Conservation Strategy. (2016). Retrieved from: https://www.oregonconservationstrategy.org/oregon-nearshore-strategy/habitats/subtidal-soft-bottom/

- Orion, Tao. (August 14, 2015). “Invasive Species Aren’t the Actual Problem, They’re merely a Symptom“. Retrieved from: Earth Island Journal

- Regan, H. (Sept. 5, 2023). “Invasive species cost the world $423 billion every year and are causing environmental chaos, UN report finds“. Retrieved from: CNN.com.

- Cunliffe, M., Murrell, J. “The sea-surface microlayer is a gelatinous biofilm“. ISME J 3, 1001–1003 (2009). Retrieved from: https://www.nature.com/articles/ismej200969

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “Human Disturbances to Estuaries“. Retrieved from: oceanservice.noaa.gov.

Thank you, Carole, for another thought provoking post! You’ve introduced a whole new vocabulary and thanks to your clear, organized explanations and descriptions I learned a LOT easily and enjoyably! Standing at the edge of a lake or the ocean, it feels like the vastness of the water and space could buffer any challenge that may come along. But, in reality it is a very fragile system dependent on many elements, some within our control and others not.

Thanks again for your research and post~ Nancy

LikeLike

Thank you for reading and commenting, Nancy. I’m pleased that you got something out of it.

Carole

LikeLike

Love this! Really opened my eyes to the richness of something I’d overlooked!

LikeLike